The Vocation of the Hospice Nurse: A "Midwife for Souls"

Health: Issue One

Kathy Kalina, Midwife for Souls: Spiritual Care for the Dying (Boston: Pauline Books & Media, 2007).

“We are eyewitnesses to the infinite value of the last days. We see the miraculous spiritual growth and reconciliations, the heroism, humor, and unconditional love of the dying. We feel the graces that flow and, if we’re attentive, we see the eyes of Jesus. Even if the whole world insists that killing can be an act of mercy and compassion, hospice midwives must stand firmly and boldly in the defense of life, from womb to tomb. It’s nothing less than our duty to speak the truth we’ve been blessed with." - Midwife of Souls,p. 75

It is precisely this eyewitness account of the infinite value of the last days which seasoned nurse and hospice care practitioner Kathy Kalina offers to her readers in her book Midwife for Souls: Spiritual Care for the Dying. Comprised mainly of stories from her own experience with the dying, this work grants a rich and privileged perspective into the mysterious beauty of the last days of life. Although written primarily as a guide for hospice workers and those who live with the terminally ill, the vignettes contained therein testify powerfully to all readers about the inviolable sacredness of the soul’s final journey to God, and offer practical wisdom on how to accompany a loved one during the last days of this pilgrimage.

The author begins by sharing her original reluctance to become involved with hospice care, rooted in her distasteful experiences of hospital practices regarding death. In her time as a nurse she had seen numerous patients who, though clearly past the point of being able to be cured, were made to endure painful and unnecessarily prolonged treatment. Believing there must be a better way in which to accompany the dying she came to appreciate the contrast she found in hospice which, in focusing on the control of symptoms rather than the cure of the disease, offers the patient the opportunity to die in the peace of their own home surrounded by their family. She states that “care for the dying has traditionally been a function of the family with generous community support.” However, because the geographical scattering of families and communities has resulted in a general ignorance about how to care for the terminally ill, she believes that “the hospice team can fill these gaps, acting as a substitute for family wisdom and community support, giving families the courage to care for their loved ones at home.”

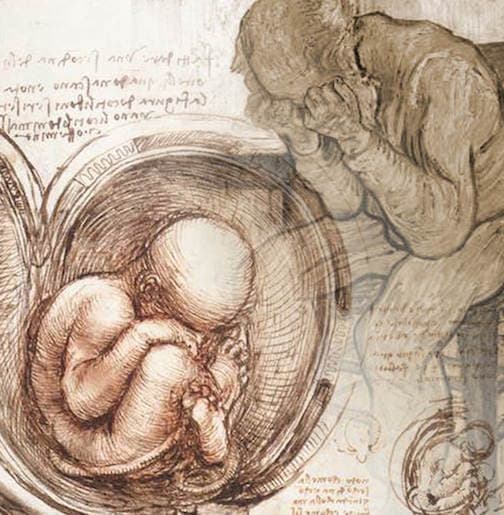

In order to articulate the nature of a hospice worker’s task, Kalina returns over and over to the analogy which she sets forth in the title of her work: namely, that the hospice nurse acts as a ‘midwife’ of the soul in its transition from life on earth to eternal life. She points out that the word ‘hospice’ means “a place of rest for weary pilgrims” and seeks to enlighten her readers about the arduous spiritual work that takes place in souls preparing to meet God. She insists that the hospice care worker must be concerned the whole truth of the person, understood as a body and soul unity who exists in relation with others, and is ultimately called to communion with God. “In midwifery for souls, the goal is a comfortable body, a peaceful passage and a triumphant soul”. To this end she educates the prospective hospice care worker on the physical, emotional, relational and spiritual needs of the dying patient.

Regarding the physical needs, she focuses primarily on the role of the hospice midwife as ‘comfort expert.’ She tells us she always starts there because “trying to work on anything else before the patient has reached some level of comfort is futile.” Additionally, she helps the ‘midwife of souls’ to recognize some of the physical signs of the imminence of death in order that she might assist in preparing the family for their final farewells.

In contrast to the common practice which counsels those who work with the terminally ill not to allow themselves to become emotionally attached to their patients,Kalina insists on the need for the hospice nurse to allow herself to bond with the patient. When an emotional connection is formed between the caregiver and receiver, it enables the hospice worker to accompany and support her charge in their emotional needs. She finds that patients often have a longing to tell their story and to speak of their faith and their fears. To this end she offers several leading questions which help facilitate conversations, such as, “How long have you been sick?”, “Are you afraid?”, “What do you think will happen after you die” or “Do you believe in God”? In the face of a patient’s anxiety, she is able to share from her own treasury of experiences in order to assuage their fears about death. “I share what I’ve seen with my own eyes. I tell them about patients who saw angels and loved ones already on the other side. I tell them about patients who die with an expression of radiant joy, who obviously are seeing something beautiful at the moment of death. And then, with their permission, I pray with them.”

An integral part of caring for the whole person involves recognizing that the patient is not an isolated individual but rather one who exists in relationship. Kalina insists that the family is ‘the basic unit of care’ and stresses to all hospice workers the necessity of working closely with the family and listening to their needs and concerns. She testifies that when the family is able to participate in the physical care it can bring relational healing and help reconcile them to their loved one’s death. The importance of the intimate relational dynamics which occur during this time, even when a patient is seemingly unconscious, is demonstrated in some of the remarkable stories the author shares of patients refusing to die until certain family members are present, or until they receive permission to die from their loved ones.

Above all, Kalina stresses the importance of the spiritual care for the dying. She encourages her ‘midwife of souls’ to assist in getting clergy involved and to look for opportunities to pray with the patient. In the appendix she includes some prayers and scriptures that can be helpful in bringing spiritual comfort to those who are dying. She remarks that the physical signs of approaching death are accompanied by spiritual signs such as desire for silence, detaching from relationships, and a spiritual restlessness which, when it passes, is usually followed by a new peacefulness and resignation. In addition she notices what she speaks of as a ‘heightened spiritual awareness’ at the approach of death, marked by patients staring intently at some point in the air and speaking of seeing angels or loved ones, or even at times menacing presences which have come to try to rob them of their confidence in God’s love. In the intense vulnerability of the dying process, she is convinced that patients “want to believe in a loving and forgiving God, and as a Christian midwife for souls it would be irresponsible not to gently share my faith with them when presented with the opportunity.” She has found that when patients bond with their hospice nurse, they let her in on the process of reviewing the joys and regrets of their life. When allowed into the sacred space of this ‘life review,’ those at the bedside of the dying can be a catalyst for encouraging them to reconcile and forgive past injuries in order for a peaceful death to occur. Finally she speaks of the need for the hospice midwife to attend to her own spiritual needs through prayer, personal formation, and fellowship with other believers in order to better be an instrument of grace to those whom she severs.

Via the witness of her own experience at the bedside of the dying, the author argues passionately against the practice of assisted suicide and euthanasia. She insists, “If a patient takes an unusual amount of time to die, there is always a reason. Even if you can’t figure it out, there’s important work going on. That’s why euthanasia is such a tragedy, aside from the fact that it’s murder. It robs the patient, and the family, of the time they need to resolve vital issues, even if they can’t see any purpose to the delay.” In her work she finds that suicide requests usually come only when a patient is suffering from uncontrolled pain, coupled with a sense of being burdensome or unloved. Hospice seeks to address both of these concerns in order that the patient and family may receive all the blessings of reconciliation and growth in spiritual maturity which God has prepared for them in this final time. In accord with her theme, she likens suicide requests to a woman in labor who tells her midwife she wants to give up and go home before the child is born. She asserts that the midwife of soul’s job is to dissuade patients from giving up the fight and encourage them to push through to the end, while likewise assuring family members tempted to hasten their loved one’s death that “killing her would rob her of the time she needed to put her house in order.”

Additionally, she addresses the crucial distinction between the withdrawal of food and water for the purpose of hastening death, and the point when food and water can no longer be processed by the body. In a footnote on page 12 she clarifies, “[I]n the active dying process, the body’s systems are failing and eventually lose the ability to process or to utilize food and fluids. In this case the patient will take in by mouth only what the body needs. Tube feedings and IV fluids strain marginally functioning systems and cause discomfort. This is not to be confused with removing food and fluids from an unconscious patient—whose body is able to utilize nutrients—in order to cause death.” While some hospice programs have been known to intentionally render the patient perpetually unconscious through medication and consequently allow them to starve to death through being unable to wake up in order to take food, Kalina in contrast argues forcefully for a hospice care in which “death is neither hastened nor prolonged,” in conformity with the full truth and dignity of the human person.

Finally, Kathy Kalina concludes her work with a word on the mystery of suffering, which is inextricably linked to the end of life issues to which she is speaking. The foundation of her rejection of what she calls the “false kindness without love” which seeks to kill the sufferer, is the conviction that suffering in union with the Crucified Lord is “infused with the ‘salvific power of Christ’s own Cross, offered to humanity in Christ’”. Going back to her midwife motif she writes, “Working in labor and delivery would be very depressing if you never saw a baby. Hospice midwives must see the baby, the soul, safely delivered to God, with their spiritual eyes.”The revised edition of this book includes an additional section of stories which testify gloriously to the “spiritual productivity of suffering,” in which she has seen her patients “lifted by that grace to spiritual maturity, even greatness which inspires those around him or her.” Likewise, it is faith in the fruitfulness of suffering love that enables her to repeatedly embrace the compassionate grief intrinsic to her work. She explains, “It took me years to discover the truth; the only way to protect yourself from the pain of compassion is to never love. For a midwife of souls, that just isn’t an option.”She has come to believe that offering the gift of one’s presence at the beside of the dying in imitation of the loving Mater Dolorosa in attendance at Her Son’s death can be a manifestation of what John Paul II in Savifici Doloris speaks of as the “gift of self,” through which one “finds himself” as he grows toward the fullness of his humanity. “Did you know that a heart can get stronger in all the broken places?” she writes. “I used to think it took a strong heart to do difficult things. Now I know that doing difficult things is how you get one.”

In summary, I believe the stories which Kathy Kalina shares in Midwife for Souls : Spiritual Care for the Dying do exactly what she intends them to do: namely, offer encouragement and practical advice for all who live and work with the terminally ill. She is explicit that she is offering her readers practical wisdom for hospice work that is unabashedly informed by her Catholic faith, and which prioritizes the care of the soul in its attentiveness to the needs of the whole person. Her simple and narrative style is not intended as a theological or ethical treatise on the end of life issues, and yet the experiences of the dying which she recounts speak for themselves of the marvelous dignity of the human person. Whether it be John who beyond all odds waited weeks for his mother to arrive before he died, Mary who passed peacefully moments after she was finally able to forgive her ex-husband, or four-year-old Brice telling Jesus that he wanted to bring his puzzles and his grandmother along when he went, each show forth the relational reality of the human person, created with free will and called to union with God. Additionally, the author’s sensitive and maternal approach to addressing the needs of the dying offer a helpful example and encouragement for all who find themselves timid before the unfamiliar challenge of facing the death of a terminally ill loved one. Finally, as one who must likewise make this same journey common to all who share the mortal condition, I am grateful for, and deeply comforted by, the numerous stories Kathy Kalina shares in Midwife of Souls of the merciful tenderness and nearness of God to the one preparing to meet Him. “Since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses, let us rid ourselves of every burden and sin that clings to us and persevere in running the race that lies before us while keeping our eyes fixed on Jesus, the leader and perfecter of faith [who] for the sake of the joy that lay before him ... endured the cross despising its shame, and has taken his seat at the right hand of the throne of God … in order that you may not grow weary and lose heart.” Hebrews 12:1-3

Kristine Cranley is a PhD student at the John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family.

Posted on August 19, 2014