When Lean In came out, it was as though a cork had been forced back into a bottle that had begun to bubble over. A high-ranking director in the State Department had just stepped down to return to her job nearer to home—and her two teen-age sons. What is worse, she had dared to write about it in The Atlantic Monthly (in July 2012) in an article entitled “Why women still can’t have it all,” offering in response an unconventional answer. The reason she suggested was not chiefly found in outside male forces inimical to women and their advancement—but in women themselves who don’t appear even now to think the same way about being away from their children as do men. “Deep down,” wrote Anne-Marie Slaughter, “I wanted to go home . . . [not just that] I needed to go home.” And she would not go alone. Launching the “happiness project,” she rallied her feminist sisters: “Let us rediscover the pursuit of happiness, and let us start at home,” she cried. That was the message that Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In manifesto came swooping in to put back into the bottle. There was no place for the wisdom and experience of older feminists, garnered after years of putting off having children, and not being with them (if and when they had come along). There was no room for questioning the terms of “equality,” measured as they were by boardroom and C-suite statistics, only new resolve to stay on task and resist the urge to “lean out” when the baby was due or desired by recommitting to the (one legitimate) cause—career advancement—choosing the right partner and sequencing things correctly. It was in the wake of these “half-truths,” that Slaughter decided to pick up where she left off when she popped the cork with her provocative article.

Unfinished Business: Women Men Work Family, Anne-Marie Slaughter’s 2015 book,is in many ways a welcome breath of fresh air much like her earlier article. When a woman such as Slaughter “comes out of the closet” acknowledging her unexpected desire, however un-orthodox, it gives women who are no longer willing to put their whole lives at the service of the (one) goal a little breather. It makes them feel not so out of step when they read her account of a young millennial’s confession: “I don’t want to go to grad school. I don’t even know if I want a career. I want to get married stay at home and raise my kids. What’s wrong with me?” (124). They feel a certain liberation from all the denial—personal and cultural—in the face of the book’s realism about “sequencing” (however painful). “Life doesn’t go as planned,” the author tells us soberly. And even apart from external obstacles to set goals, there is the simple fact that, from the point of view of a woman’s actual body, the (one) sequence—terminal degree, established career, capstone marriage, then maybe a baby—is, well….out of sequence.

Beyond providing a little relief for weary feminist pilgrims, the book also probes and challenges some of the cultural habits of thought and practice. As for the first, Slaughter points out the general underestimation and presumed inferiority of the care of children, telling us how difficult the work is and how much intelligence it requires for the person who can “respond in the moment, dynamically, [with] analytic skills, executive function, ordering and sequencing, and ... a lot of information” (105). While some of the care-giving expertise Slaughter brings forward sounds rather . . . un-caring, what Milton Mayeroff offers her hits the mark. “Caring,” he says in his book On Caring, “is a work akin to that of an artist who has an idea but then has to follow the grain of the wood or the fissures in the stone, or the characters of the story. Essentially, to care is to shape and guide someone who is not entirely within one’s control, based on a deep commitment to and knowledge of him” (112). Slaughter doesn’t know about Saint John Paul II’s “feminine genius,” but the insight and re-evaluation of caring which resembles it, however generically, has her “happily [if cautiously] embrace gender differences” (149).

Unfinished also takes on the workplace itself which, in its dominant mode, is everything one would expect in a society where the care of the most vulnerable is considered unimportant. It is the world of the ideal worker with a good work ethic, namely the one who is the first to arrive, last to leave, never sick, never takes a vacation, and is essentially available 24/7. Sensitive to criticisms coming from left field—Susan Faludi, for example—about white feminists who have sold their souls to the “company store” by letting the store establish the benchmarks of success for women, Slaughter proposes that the store be renovated. For Slaughter that means that the workplace listen to the “different voice” more typical of women. A woman’s “lack of focus,” for example, is for Slaughter exactly the kind of antidote needed for the tunnel vision of Homo economicus who has no emotional baggage. As a case in point she brings forward new findings about women traders, who make better long-term decisions with their careful analysis than do their rapid-fire male counterparts.

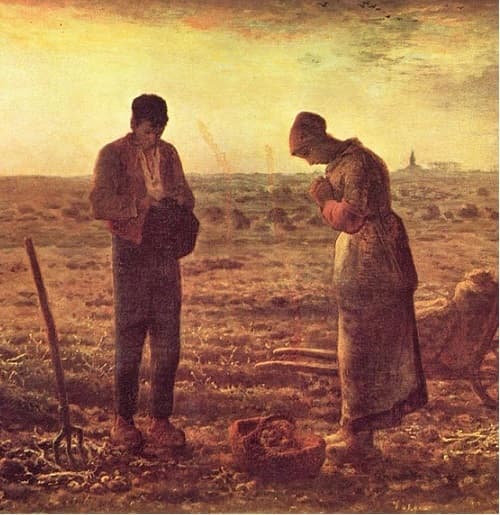

And if, for Slaughter, the workplace would be better off populated with more women, it follows that the home would be better off with more men taking care of some of the “care.” After all, she argues, science has now discovered that men are affected biologically by becoming fathers in ways that “wire” them to their children, just as women are by their better-known “love hormone” (the oxytocin released during labor and breastfeeding). And from the historical point of view, she reminds us, it wasn’t so long ago—before the workplace and the homestead were set apart—that children apprenticed with their fathers on farms and in workshops. In sum, each place, the workplace and the home, would benefit from both men and women being there.

Slaughter does well to criticize the too stark division of labor which took work (and men) away from the vicinity of home and made the home the “comfortable concentration camp” that Betty Friedan described. That said, however much we might welcome a greater proximity of men and women in their day-to-day lives, it isn’t clear that the business Slaughter wants to “finish,” going forward, isn’t going to drive an even deeper wedge between work and home, to the point of absorbing the latter. It is not enough to put men and women next to each other in the same workplace and on equal shifts at home (after overcoming the care stigma), as Slaughter proposes. The real question is whether the world of work will serve the common good that men and women generate together and live out in the most paradigmatic way in the home, where the good of its members is bound up quite literally with the good of the other. If that is the object of work, then there will be no problem accepting the differences in the way men and women work—akin to the way they generate children. If it is not, then there will be. And work will be about equal possibilities for “personal fulfillment,” as one chooses it.

That question is what drove John Paul II to promote the “feminine genius”—the “special openness to the person” (Mulieris Dignitatem,18) that a woman has in virtue of her capacity to be a home for the child, making room for it, letting it grow. . . letting it be. Because of dominant cultural tendencies that make the world un-homelike—tendencies in social organization and management that crush the humanum under the criteria of efficiency and productivity (Letter to Women, 4)—the Holy Father thought that this “genius” had to be acknowledged and “brought forward” in a particularly urgent way. He proposed this, we should add, not merely to temper the hectic pace of the workplace and promote more long-term decision making while leaving the current terms of work—the “bottom line”—and the consumer economy largely unaffected (as Slaughter appears to do). But to turn work and the economy toward their proper ends: the promotion of goods and services that serve the proper good of the human being, making him more at home in the world. (The first meaning of “economy” is “household management.”) This “genius,” moreover would do this asit made the home more, not less of a home. But the latter is one of the likely effects of Slaughter’s “unfinished business.” What is ultimately a genderless care reform proposal for Slaughter—after paying all the predictable respects to a culture which has now made interchangeable “parents” the norm, and reduced the “biological imperative” for women to the bare minimum, if that—becomes for her very quickly a parentless one. However much she enjoins men to consider “primary care giving” too, in the end, what Slaughter looks forward to is a “care economy,” in which children would spend the few remaining hours of free time left in an “infrastructure of care,” in organized “educational” activities with “highly trained,” and better-paid, employees, that is. The home, as a result, would become ever more what it has already become, an address where people sleep, entertain themselves, open and heat their meals, receive Fed Ex packages, and “consume a large quantity of merchandise and a large portion of each other,” as Wendell Berry put it. Instead of recovering what was lost after the much-maligned Industrial Revolution—by recovering the home as a place that generates society, including its economy—the proposal would continue to absorb what little was left behind into the newer (digital) corporate marketplace while putting “care” into the hands of interchangeable wage-earners in that marketplace. As a result, the workplace would be even more deprived of a view of the common good and generate an even more un-homelike economy.

Perhaps the real “unfinished business” is to follow through with the experience that Slaughter had in the first place and ask: after all of the energy we have spent bringing down “social constructs,” why is it that women still have a different—even if not exclusive—relation to “care,” wanting to go home, not just needing to? And if there is a reason other than those resistant “stereotypes” offered almost unanimously (including by Slaughter), might we consider a different idea of equality than the one that dominates American culture: the one that that flattens out of all the differences, shutters all our homes, and institutionalizes all our children? One that can really put men and women together—not just on parallel tracks, but in a fruitful, human, and more home-like economy?

Margaret Harper McCarthy is an Assistant Professor of Theology at the John Paul II Institute and the US editor for Humanum. She is married and a mother of three.

Keep Reading! The next article in the issue is, Out of Work: The Tragedy of "Un-Working" Men by Brian Rottkamp