It was Pope Benedict XVI who, in Caritas in veritate (2009) turned our attention to “human ecology” when he said: “The book of nature is one and indivisible: it takes in not only the environment but also life, sexuality, marriage, the family, social relations: in a word, integral human development” (51).

In its first three issues on ecology, Humanum has probed the question of man’s relation to the natural environment. It did this with an eye to what Pope Francis called the “dominant technocratic paradigm” (Laudato Si’, 101) where it is as if “the subject were to find itself in the presence of something formless, completely open to manipulation” (106). (There is also the “biocentric” reaction to this “anthropocentrism,” which puts into question the unique role that man plays as a steward of the natural world.)

Now we turn to the environment that man is and the one in which he dwells―the body and the home―the environments in which he was first welcomed and into which he, in turn, will welcome others. We do this with a certain urgency, because, as is plain for all to see, the dominant paradigm has been turned on the very subject using it. It is as if the new image of action, material and product had redounded back on the actor, in keeping with the Scholastic axiom (if not the Scholastic conception): omne agens agit sibi simile (every agent causes something similar to itself). We have heard the warnings, most memorably, from C.S. Lewis:

The final stage is come when Man by eugenics, by pre-natal conditioning, and by an education and propaganda based on a perfect applied psychology, has obtained full control over himself. Human nature will be the last part of Nature to surrender to Man. The battle will then be won. We shall have “taken the thread of life out of the hand of Clotho” and be henceforth free to make our species whatever we wish it to be. The battle will indeed be won. But who, precisely, will have won it? (Abolition of Man, 72)

And there is no lack of similar concern for the mechanization of the human being today. Take for example the book (and more recent film) The Giver, reviewed here. The idea of a human world deprived of memory and emotion, of children conceived, selected, distributed, and disposed of in sterile white laboratories―“rationally”―horrifies us.

And yet, we hurtle on as we march for “reproductive rights,” the euphemism for that same “rational” conception, selection, distribution and disposal of children in those same sterile white laboratories―not to mention the arresting of female health itself. And while we are at it . . . the health of children whose perfectly healthy bodies are being subjected to puberty blockers, surgical castration and other such subtractions, additions and re-arrangements. In short, talk about the respect of the environment “inside us” has not only not caught up with all the talk of respect for the natural environment “outside us”; it is very quickly losing ground.

What we are witnessing, and complicit in, then, is a sort of environmental inconsistency. As Pope Benedict XVI put it: “the manipulation of nature, which we deplore today where our environment is concerned, now becomes man’s fundamental choice where he himself is concerned.”

Perhaps, though, this environmental inconsistency with respect to ourselves is no mere oversight. As Pope Francis has suggested, it may come down to the fact that we “no longer know how to confront [sexual difference].”[1] Putting it more bluntly, we don’t want to confront it. It is one thing to confront a tree; it is quite another to confront all the relations your body puts you in!

The environmental “inconsistency” is one of our central concerns in this issue. To help us to understand it we have invited a professional environmentalist to take up the issue of population control (contraception and abortion), especially insofar as the case made for it is ecological in nature (the reason for which many would-be ecologically minded people simply aren’t). Then too we have invited the Irish author, one-time rock 'n' roll writer, and former newspaper columnist to make the case he made in Ireland two years ago, and for which he paid a hefty professional price. It is that many of the ecologically-minded aren’t ecological enough, turning a blind eye as they do to the real toxic spill that has occurred―inevitably―in the wake of changes in marriage laws: the redefinition of the parent-child relationship in terms of “guardianship” contractually dispensed (and withheld) by the State, while turning the natural bond between mothers, fathers and their children into a legal non-entity. Discussing the place of sexual difference in evolutionary theory, and in evolution itself, our featured “theo-biologist,” confirms how much the latest attempt to override sexual difference is indeed an ecological disaster of the first order.

Naturally, facing the “inconsistency” requires us (always) to ask the “what is question” about the human being, especially as concerns the unity of body and soul. That unity was, of course, re-thought in modernity when it re-described the body, and its worldly “image,” as formless, and the soul as immaterial and un-animal, making the former available for the latter’s new “paradigm.” In view of this, then, we re-propose two modern classics: Leon Kass’ The Hungry Soul and MacIntyre’s Dependent Rational Animals. Each of these attempt to recover the lost unity. One shows how such a lowly thing as ordinary human hunger is “an open window to the contemplation of a world of form, civilization, and humanity inscribed into our very animal nature and which stretches, through its ordered longing, toward union with God” (as the reviewer, Michael Hanby writes). The other shows how that same lowly animal nature is found in the uppermost regions of human reason: in the form of “virtues of dependence” involving of reception, gratitude, and vulnerability.

Finally, in an attempt to resolve the contraction, Humanum enters into the specifics of what it means to confront our own ecology, especially insofar as it is an “environment” for others. We are therefore featuring a new program to promote women’s health based on fertility awareness (overturning the current contraceptive cure-all approach) written by the founder of World Youth Alliance (an NGO present at the U.N., the European Union and the Organization of American States). There is also a review of books on breastfeeding presenting the recent conversion to breast milk, and all the expected (feminist) reservations about actual breastfeeding.

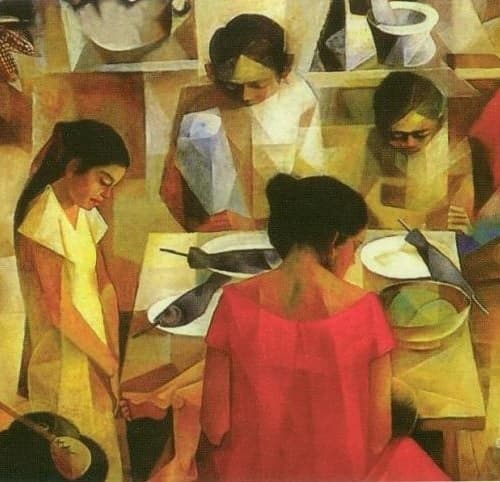

And, since the home where we live is an extension of the home that we are―especially for the woman―there is a beautiful piece on the lost art of homemaking. You will also enjoy reviews of two books on one of the privileged activities that take place in the home: eating and drinking and feasting with guests: the new “cocktail-manual,” Drinking with the Saints, and an older classic by Josef Pieper on festivity, In Tune with the World. Finally, looking at another essential activity in the home―the education of children―the review of Rachel Carson’s eco-classic The Sense of Wonder returns us, through the eyes of the child, to the vision that animates our entire ecology year: keeping our sense of wonder alive in the face of the great community of beings to which we belong.

Buon appetito!

[1] General Audience from April 15, 2015 (later cited in Laudato Si’, 155 and Amoris Laetitia, 285).

Margaret Harper McCarthy is an Assistant Professor of Theology at the John Paul II Institute and the US editor for Humanum. She is married and the mother of three teenagers.

Margaret Harper McCarthy is an Assistant Professor of Theology at the John Paul II Institute and the editor of Humanum. She is married and a mother of three.

Posted on February 12, 2017