It is almost a truism that life in our contemporary period is characterized by a profound sense of fragmentation. Our daily lives and our psyches seem to splinter in the face of the myriad responsibilities and concerns that beset us—a list that gets longer, more complex, and more fraught with risk every day. We feel pulled in every direction, even as we sometimes choose to take on more and more in the eager desire to better ourselves and the lives of our families.

All this has led to the now widely broadcast struggle to maintain some kind of “work-life balance” and the search for “mindfulness” and inner peace. Many flock to yoga classes and meditation centers, while publications claiming to provide the antidote crowd bookshelves and bedside tables. An entire business model has developed around helping us to find the path; the self-help industry generates more than a billion dollars annually in the United States alone. When the popular self-help guru Louise Hay died at 90 earlier this year, she had published more books than had almost any other woman in history. She was admired and read by countless devotees. Her multi-million dollar publishing empire grew by devoting itself exclusively to spreading what her New York Times obituary referred to as the “self-help gospel.” Widely acknowledged as the “Queen of the New Age,” Ms. Hay was perhaps most famous for her pithy, if vague affirmations such as “Life loves you” and “Every thought we think is creating our future” and “It is safe to look within.”

Though we might scoff at these pursuits, we would be mistaken to deny the impulse at their core. Even those of us who pray daily and avail ourselves regularly of the sacraments recognize that we confront the same sense of fragmentation: the existential divide between who we are and what we do. Whether in the home or in the world, whether doing the dishes or teaching a class, whether mowing the lawn or running a company, the minute I turn my attention to the task at hand, I lose contact with the reality of my own being—and that of the God who whispers to me in its depths. There is a gap between my life in Christ and my work in the world.

When Pope St. John Paul II issued his encyclical on human work, Laborem Exercens, in 1981, I was employed in the business sector as an internal management consultant; I spent the first half of my adult life working primarily in manufacturing companies. Though I was Catholic, I knew little about the Church’s vast intellectual treasury other than what I happened to receive in the Sunday homily. But a question began to develop during those years of contact with the world of work, one that grew and persisted. In the end, it was a question that would not leave me in peace: Why, I asked myself, do people tend to go to Church on Sunday and work on Monday and live as though the one has almost nothing to do with the other? I set off to graduate school to investigate, only to find that the Church had been there before me. While everyone else has been searching for inner peace in the wisdom of the East, the Catholic Church had possessed the answer all along.

In his 1988 document on the vocation and mission of the laity, Christifideles Laici (CL), Pope St. John Paul II points to two temptations that lay people often have difficulty avoiding; both serve to prevent them from realizing their vocation in the world. The first is that of being so interested in Church services and tasks “that some fail to become actively engaged in their responsibilities in the professional, social, cultural and political world” (CL, 2). The second—and perhaps of more interest to us here—is the temptation to legitimize “the unwarranted separation of faith from life, that is, a separation of the Gospel’s acceptance from the actual living of the Gospel in various situations in the world” (CL, 2). We walk a narrow road it seems between two extremes: on the one hand, a reluctance to leave our prayer corner in order to engage and transform the temporal order; on the other, a tendency to forget that we must bring the fruits of that prayer into our efforts in the world.

These two temptations are to be avoided at all costs, because the laity actually do not have the luxury of lingering in the comfort of their prayer corner any more than they have the right to go on about their business without a thought for the salvation of the world. For as St. Paul tells us—and anyone with the eyes to see knows—creation itself is waiting to be delivered from the bondage of corruption (Rom 8:21). And, according to the teachings of Christ’s own Church, it is the task of the laity to transform the world. This particular commission is not given to the priest or the deacon, nor is it given to the religious sister or brother. It is given—in clear and unequivocal terms—to the lay faithful. Indeed, according to the Second Vatican Council, “…the laity, by their very vocation, seek the kingdom of God by engaging in temporal affairs and by ordering them according to the plan of God.[1] Through our efforts, we not only provide for ourselves and our families, we participate in bringing all of creation into “the liberty of the glory of the children of God” (Rom 8:21).

In Christifideles Laici, St. John Paul II reiterates and affirms this teaching, stating that this particular mission and vocation is unique to the laity” (CL, 15). However, here he adds a new emphasis—a clear sense of heightened urgency—and a plea for action. He declares that “a new state of affairs today both in the Church and in social, economic, political and cultural life, calls with a particular urgency for the action of the lay faithful. If lack of commitment is always unacceptable, the present time renders it even more so. It is not permissible for anyone to remain idle” (CL, 3). It is no longer an option—if it ever was—to bask in the warm light of grace that comes from frequent prayer and reception of the Eucharist. In virtue of our baptism, we participate in the three-fold office of Christ (CL, 14). We are responsible for bringing his light into the world.

Here we arrive at what may be the riskiest aspect of our complicated lives. For the implication is that our faith actually obligates us to manifest it and express it in everything we say and do. We have no choice but to bring it into the murky glare of the public square.

When I finally encountered Laborem Exercens (LE), St. John Paul’s encyclical on human work, I was stunned to find articulated there what had been until then a mostly inchoate intuition: that work has a deeply theological meaning. For there he states unequivocally that our work, whether in the home or in the public sphere, actually enters into the process of salvation itself (LE, 24). The “unwarranted separation of faith from life” is not merely an incidental concern, something we simply accept with resignation in the face of the human condition. It is the central concern in our wish for wholeness and for holiness. The inner peace we seek will be found when we fully occupy the place that is uniquely ours—and grasp that its locus is in the world.

John Paul’s insights in Laborem Exercens revolve around a fundamental distinction he makes between the objective and subjective dimensions of work. Since work is both a transitive and intransitive activity, it operates in two directions. Clearly, it creates objective results external to the worker (a meal, a report, a well-made bed, an essay); we are most familiar with this aspect of work. But, he points out, it also has a profound impact on the personhood of the worker; this is the subjective dimension. The dignity of work is found most fully here, in the fact that the one doing it is a person. And so, human work must serve to recognize the person’s fundamental humanity and to permit him to become that person God had in mind for him—even before he was in the womb. John Paul’s argument is that we become who we are meant to be, in part, through the work that we do. Our work, like our prayer life, like our participation in the sacraments, is one of the means by which we move toward our real destiny, final communion with God. It is not merely a place to achieve an external result; it is where we live out our call to life in Christ.

In his encyclical, John Paul points out that all human acts, including work, are always the act of a person who is a conscious being, “capable of deciding about himself with a tendency toward self-realization” (LE, 24). The late Holy Father declares that since work is an actus personae, the whole person—body and spirit—participates in the act of working which thus can and should lead, much like other human activities, to a closer relationship to God and a deeper friendship with Christ. Through an “inner effort on the part of the person, guided by faith, hope, and charity, work is given the meaning it has in the eyes of God”—and “enters into the salvation process on a par with the other ordinary yet particularly important components of its texture.” [2]

This profound understanding of work reveals that it cannot be reduced to something I do simply to survive. Nor is it something I do merely to further a career. Work is—or can be—a vocation, a call in the midst of life, and a route to becoming whom God meant each of us to be. It is a locus of grace and of our hope in redemption. It is an aspect of our own movement back toward God, an element in our own redemption. Through it, we are able to join our sacrifice to that of Christ on the Cross and participate with him in the redemption of the world.

Ultimately, our work calls us to imitate the work of Christ himself, who performed, obediently and willingly, “the work of salvation that came about through suffering and death on a cross” (LE, 27). And so we see that it is not only through our lives of prayer and worship that we show ourselves to be true disciples of Christ, but also through our work. For there we live out concretely our participation in the three-fold office of Christ: by accepting to make the sacrifices necessary to perform our own daily tasks well, by courageously bearing witness to the truth when the opportunity presents itself, and by our efforts to take dominion, first over ourselves, and then—though our work—to transform the temporal order.[3] These are all actions that must be taken out of love, first for Christ, and then for those we serve. In so doing, we work in union with Christ on the Cross—joining ourselves to his sacrifice—and collaborating with the Son of God for the redemption of humanity and the return of all things to God. Our work, along with our praise, worship, and thanksgiving, is to be offered to God. It is to be made holy, a worthy sacrifice. It is what we bring to the sacrifice of the Mass. It is our gift—in truth, the only one we have to offer. Ultimately, it is an offering of ourselves.

The connection we are seeking becomes clear and unambiguous when we consider the words said by the priest as he prepares with us to offer the sacrifice of the Mass: “Blessed are you Lord, God of all Creation. Through your goodness we have this bread to offer, which earth has given and human hands have made. It will become for us the bread of life.” The same offering is made of the wine; it also is something that “human hands have made” and it becomes our “spiritual drink.” This prayer reveals a profound truth, something that has been obscured by time and the accretions of ritual: it is at the sacrifice on the altar where we join our work to the sacrifice of Christ and participate in the Redemption of the world.

This is somewhat easier to see by considering the historical context. In the early Church, when the Christian community was one—when pretty much everyone participated in the weekly celebration of the Eucharist—and certainly well before we could go out and purchase those perfectly identical unconsecrated hosts—the people would bring the fruits of their labor—the bread and the wine—to the back of the church before Mass. This became the matter of the sacrifice, transformed by the hands of the priest and the action of grace into the body and blood of Christ.[4]

Over the centuries, we have lost touch with the deep connection between work and the Eucharist. Perhaps because the “fruits of our labor” are so often collected at the beginning of the Offertory, our gift of currency gathered by ushers, taken, often somewhat surreptitiously, up the side aisle, while someone else walks down the center aisle to give the bread and wine to the priest. The gift of the people, meant to be joined to the body and blood of Christ, is handed off to the closest lay minister who unobtrusively passes it along to someone in the sacristy. While understandable in light of modern day realities, this practice has helped us forget that what is offered at Mass is our work—in the form of bread and wine—and that it is in the Eucharist that that our work joins with the sacrifice of Christ in an offering to the Father.

But let us be clear here. If we are to take John Paul’s account seriously, it is not merely the objective results of our work that are offered—our dollar bills and pocket change—for it is the subjective dimension of human work that lends ultimate meaning to our efforts in the world. After all, it is through the subjective dimension of work that its objective results are created. The value of work is found in the fact that the one working is a person—and though it is true that in working I create things that can be traded or sold or shared, in that process I also am created; through it, I come closer to that fully actualized creation envisioned by my Creator—or not. And thus, it is this inner work more than anything else that is offered; it is my being, my effort to become a new creation during the week. It is our work on ourselves that becomes the sacrifice. What is offered is our becoming, our own joining of ourselves to Christ on the Cross through the work that we do.

Our work in the home or in the world is a place where we put our gifts to at the service of the kingdom, every moment of the day. Do we remember that we are always in the presence of God? Do we attend to his presence in the everyday occurrences? Do we notice the opportunity for small—or big—sacrifices?

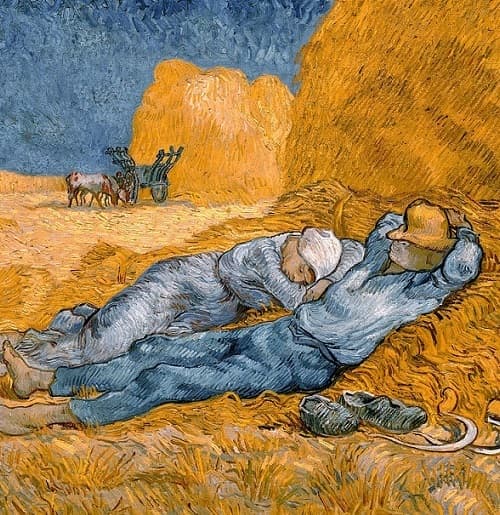

In the eyes of our Church, every moment is potentially a Eucharistic moment. The whole of creation embodies the sacramental principle because wherever we are—it is in God that we live and move and have our being (Acts 17:28). There is nowhere, not the public arena, not the workplace, not the home, not the school, not the steps of the Capitol—where God does not reign. And as Brother Lawrence so beautifully said so many years ago—we are called to practice the presence of God, whether that be cleaning a toilet, diapering a baby, cleaning out the garage, or in a meeting. We bring these little moments of sacrifice to the Eucharist, they are transformed, and they are returned to us as the Body and Blood of Christ—the Bread of Life, without whose sustenance, we cannot have eternal life.

When we toil, whether it is to provide for our families, to become “more a human being,” or to pursue peace and justice and contribute to the conditions that foster human development, we find “a small part of the cross of Christ.” And the Christian will accept this “in the same spirit of redemption in which Christ accepted his cross for us.” We go to Mass to worship, to offer our sacrifice, our thanksgiving—and to be reminded that our work must be ordered both toward our own salvation and that of the world. Our work must reflect the meaning it has in the eyes of God—wherever it takes place.

Deborah Savage is a member of the faculty at the St. Paul Seminary School of Divinity at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul Minnesota where she teaches philosophy and theology and also serves as Director of the Masters in Pastoral Ministry Program. She is the co-founder and director of the Siena Symposium for Women, Family, and Culture, a think tank organized at the University to respond to St. John Paul II’s call for a new and explicitly Christian feminism.

[1] Lumen Gentium, 30.

[2] LE, 5.24. Work is not only a sharing in the creative act of God, but also a sharing in his redemptive and sanctifying aspects.

[3] These three aspects of our working lives correspond to the three-fold office of Christ. Though it is perhaps well understood that the laity clearly participate in the priestly office through their daily sacrifices and the prophetic office through their witness, it seems to have escaped many Christians that our call to transform the temporal order is specifically a reflection of the kingly office of Christ. In light of our baptism, it is our duty to root out continually the structures of sin and disorder through the work that we do.

[4] As early as the second century, the bread and the cup were given solemn form. Soon after, the faithful brought to the church the bread and wine they made themselves to be offered at the sacrifice. St. Augustine reports in The Confessions that his mother brought her offering to the altar every day without fail. See Robert Cabie, The Eucharist: The Church at Prayer, vol. II, ed. A.G. Mortimer (Collegeville, MN: 1986), 77‒78. The Byzantine ritual retains this practice, accepting a slice from the bread offered by each family in the sacristy before Mass. This becomes the consecrated bread, offered in the sacrifice.

Keep reading! Click here to read our next article, Of Work and Home...and God's Glory.