There is a telling scene in the movie The Circle, in which a young woman recently employed by an all-encompassing social media corporation is persuaded to move her entire social life to her work-place: so that the line between her work and her personal life becomes completely blurred. This brave new world is far from being a dystopian vision: rather it feels like an all-too contemporary satire. Only a few years ago, Elon Musk, who runs the corporation incorporating both Tesla cars and the SpaceX company (which aims to establish a human colony on Mars), was heard to grumble that not enough of his employees showed up to work on the weekend.

Currently, Americans work more hours than their counterparts in any other Western nation. And yet studies at Boston University and Stanford have found that employees are not any more productive if they put in 80 hours a week than if they had worked a mere 55 hours. And researchers at the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health have found that long hours simply increase stress, depression, and heart disease. Is it not ironic that a corporation that intends to ‘save humanity’ by making environmentally friendly cars and sending members of our species to another planet, prefers to hire workers who have no family commitments: that is to say, no human context? (And yet just recently Musk pointed out that falling birth rates would impact disastrously on the economies of the West—an interesting disjoint when put next to his obsession with keeping his workers out of their homes as much as possible!)

When we consider the question of work, we therefore have to consider the context in which work is carried out. The corporate vision that is engulfing much more than just the Western world leaves precious room for a context which allows us the freedom to be fully human (let alone to know what work is for). And humanity is always contextualised by community: a family, a religious community, a network of friendships that are not purely utilitarian. Another word for this context is the States of Life. In these the question of work takes on its rightful meaning, its place in the great scheme of things. And that is what this issue of Humanum aims to explore.

We look at the relation between economics and the family, with a review of Christopher Franks’ book He Became Poor: The Poverty of Christ and Aquinas’s Economic Teachings, in which Rachel Coleman asks whether an economy in which money is the highest good might militate against the natural order in which the family finds its function and meaning. We also have Alan Carlson’s feature on Willhelm Röpke, one of the lonely free-market economists who thought the family should be placed at the center of his field, and a review of Carlson’s own book on the various 20th century attempts to actually do this!

Humanum looks also at the persons at work in the family. Margaret McCarthy reviews the latest book on the “work-life balance” issue for women: Anne-Marie’s Slaughter’s Unfinished Business. And Brian Rottkamp reviews the latest (disturbing) report on the state of work for men, Nicholas Eberstadt’s Men without Work. Sonia-Maria Szymanski gives a personal witness of the role of work—her husband’s and her own—in her marriage. Randy and Lucy Hines offer a glimpse of something that transcends the usual question about whether or not a woman should work—and the problem of men out of work—with a verbal diptych about their family business, a bakery they run together in close proximity to their home. With the Hineses we begin to get an idea of what John Cuddeback writes about in his article “In Search of the Household” where the household is both a home and a workshop.

Humanum also takes up the other state of life, the “life of the counsels” be it consecrated life in the world or in the monastery, with Léonie Caldecott’s feature on the work of Caryll Houselander and a reflection on monastic work by Dom Hardy, prior of the celebrated Benedictine Abbey at Pluscarden in Scotland. Devra Torres’s review of Josemaría Escríva’s Friends of God prolongs this reflection for the everyday life that most of us experience:

Because the world comes from the hands of God, it is primordially good. Because He left it intentionally “unfinished”—in need of cultivation and development—our work has always had its part to play.

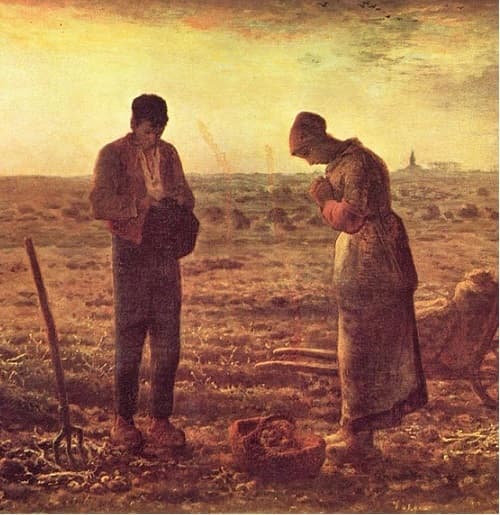

In all of this Humanum poses the following question: what does it mean for work—for the production of our “daily bread”—when it is contextualized by a vocation, a state of life? And what does it mean when it is not? For Charles Péguy’s French peasant it was unthinkable that anyone would work if it were not for their children.

All that we do we do for children.

And it’s the children who make it all get done.

All that we do.

As if they led us by the hand.

—The Portal of the Mystery of Hope, 22

This is a long way from a world of work in which everyone enslaves him or herself to the quest for status or an ever-increasing pile of consumer goods. Such things are not like children. They are not a community. They do not give life.

Léonie Caldecott is the UK editor of both Humanum and Magnificat. With her late husband Stratford she founded the Center for Faith and Culture in Oxford, its summer school and its journal Second Spring. Her eldest daughter Teresa, along with other colleagues, now work with her to take Strat’s contribution forward into the future.

Keep reading! The next article in the issue is an excerpt from Charles Péguy’s The Portal of the Mystery of Hope.

Léonie Caldecott is the UK editor of both Humanum and Magnificat. With her late husband Stratford she founded the Center for Faith and Culture in Oxford, its summer school and its journal Second Spring. Her eldest daughter Teresa, along with other colleagues, now work with her to take Strat’s contribution forward into the future.

![]()

Posted on August 14, 2017